RUDN University Chemist Suggested Synthesizing Bioactive Substances Using a Copper Catalyst

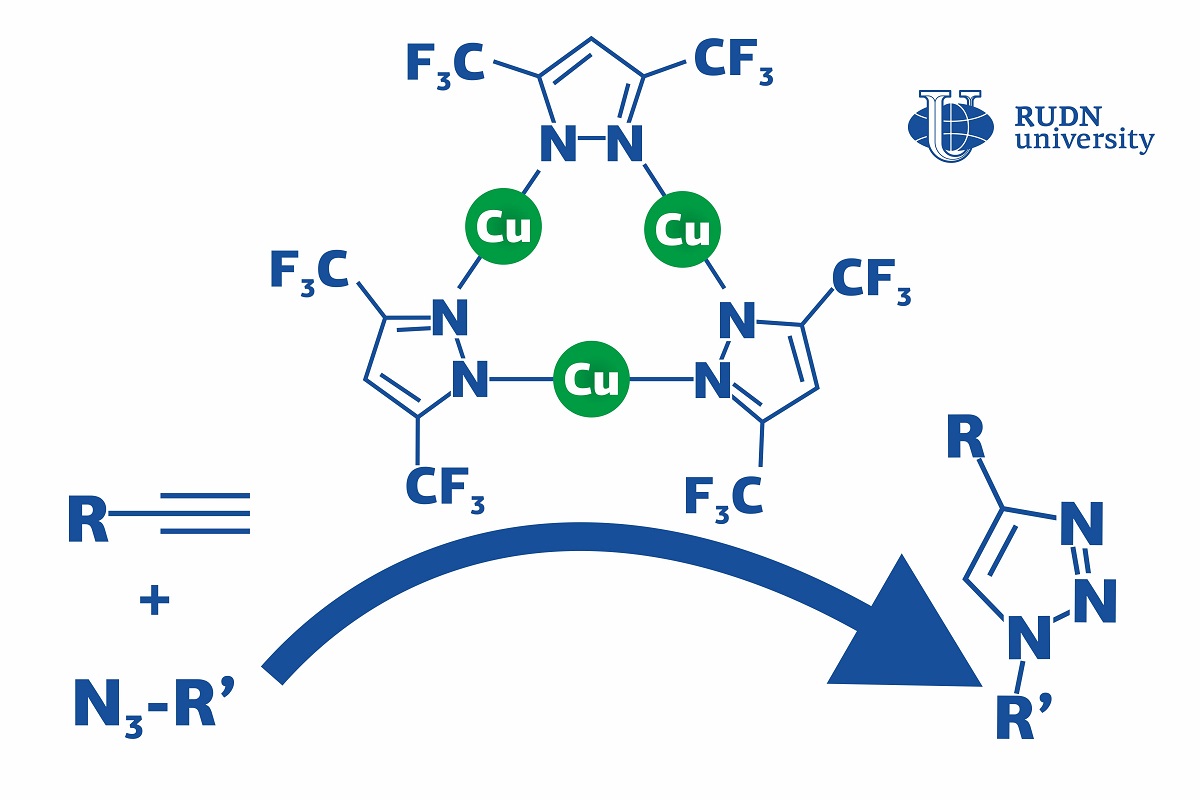

Click reactions are reactions in which simple molecules (or modules) ‘click’ together and assemble into a large complex molecule, just like details of a construction kit. They are mainly used in the pharmaceutical industry and polymer chemistry. Using the click reaction of azide-alkyne cycloaddition (or CuACC), manufacturers obtain triazoles, bioactive substances with antibacterial, neuroleptic, and antispastic properties (such as fluconazole and itraconazole). As a rule, these reactions require copper-based catalysts to speed up the process. However, they operated at special conditions (e.g. at higher temperatures or in the presence of additional chemicals) which increases the production cost. A chemist from RUDN University suggested using a copper complex that accelerates the click reaction and lets it go on at room temperatures and without an additional base. Moreover, his team developed the first complete description of the reaction mechanism that had not been fully understood before, especially for different catalyst systems.

“CuAAC can involve different copper catalysts, but in many cases, they require severe conditions (such as high temperatures, additional reagents, and so on). Although the mechanism of this reaction has been thoroughly studied, the details of the catalysis are still being discussed,” said Vladimir Larionov, a Candidate of Chemical Sciences, and a researcher at the Department of Inorganic Chemistry, RUDN University.

The team studied a chemical compound that had three copper ions bound with ligands (complex organic ions). The complex was used as a catalyst in the CuACC reaction at room temperature. Dichloromethane, toluene, and other substances were tested as solvents. However, even in their absence the copper complex let the team obtain the required reaction product in 4 hours, while without it the reaction did not happen at all. In the end, 99% of the initial substrate turned into triazole, and there were no by-products.

The team was also the first ever to study the mechanism of this reaction using mass spectrometry and quantum-chemical calculations. The molecules were broken down to charged fragments, and after that their structure was identified based on the mass to charge ratio of each fragment. The catalyst turned out to work in two ways at once: the ligand helped the alkyne lose a proton and enter an active state, while copper ions played a role in the formation of an intermediate. In the course of these processes, bonds were formed between metal ions in the catalyst and the particles of the substrates. Previously, the bond formation between the catalyst and the alkyne (i.e. copper acetilyde) had been considered the slowest step of the reaction. However, the team disproved this belief and confirmed that the formation of the first bond between two reagents sets up the rate of whole reaction depending on catalytic system.

“Our results show that the rate-determining step that determines the rate of the CuACC reaction depends on the catalyst system and reagents. Previously, this fact was underestimated enough,” added Vladimir Larionov.

An article about the work was published in the Journal of Catalysis.

Products derived from microalgae represent a cutting-edge development in the field of bioeconomy. The potential of this biological resource was discussed at the international research seminar “Foundations for a Green Sustainable Energy”, part of the BRICS Network University’s thematic group on “Energy”. The event was organized by the Institute of Ecology at RUDN University.

Ambassadors of Russian education and science met at a conference in RUDN University to discuss how they can increase the visibility of Russian universities and research organizations in the world, and attract more international students in Russia.

The international scientific seminar hosted by RUDN Institute of Ecology “Experience of participation in student organizations as a way to form career skills” united scholarship recipients of the International Student Mobility Awards 2024 and Open Doors, along with members of the scientific student society “GreenLab” and the professional student association “Kostyor (Bonfire)” shared their projects focused on environmental protection.