A Chemist from RUDN University Developed an Environmentally Friendly Method for Anti-Malaria and Anti-Leprosy Drug Production

Many think of leprosy as a disease of the past; however, about 200 thousand cases of it are registered in the world (mainly in India, Brazil, and Nepal) every year. It is treatable with antibiotics that prevent the growth of the Mycobacterium bacteria. On the contrary, malaria is one of the most widely spread diseases in the world with over 200 million cases annually. The spread of its agent (a protist from the genus Plasmodium) also can be inhibited with antibiotics. Dapsone is a safe and available drug that works in both cases and is included in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. However, its production is not eco-friendly, as the synthesis reaction requires high temperatures and the use of aggressive acids (such as sulphuric acid). A chemist from RUDN University suggested a green technology of dapsone synthesis that could potentially help expand its production and make the drug available to more patients.

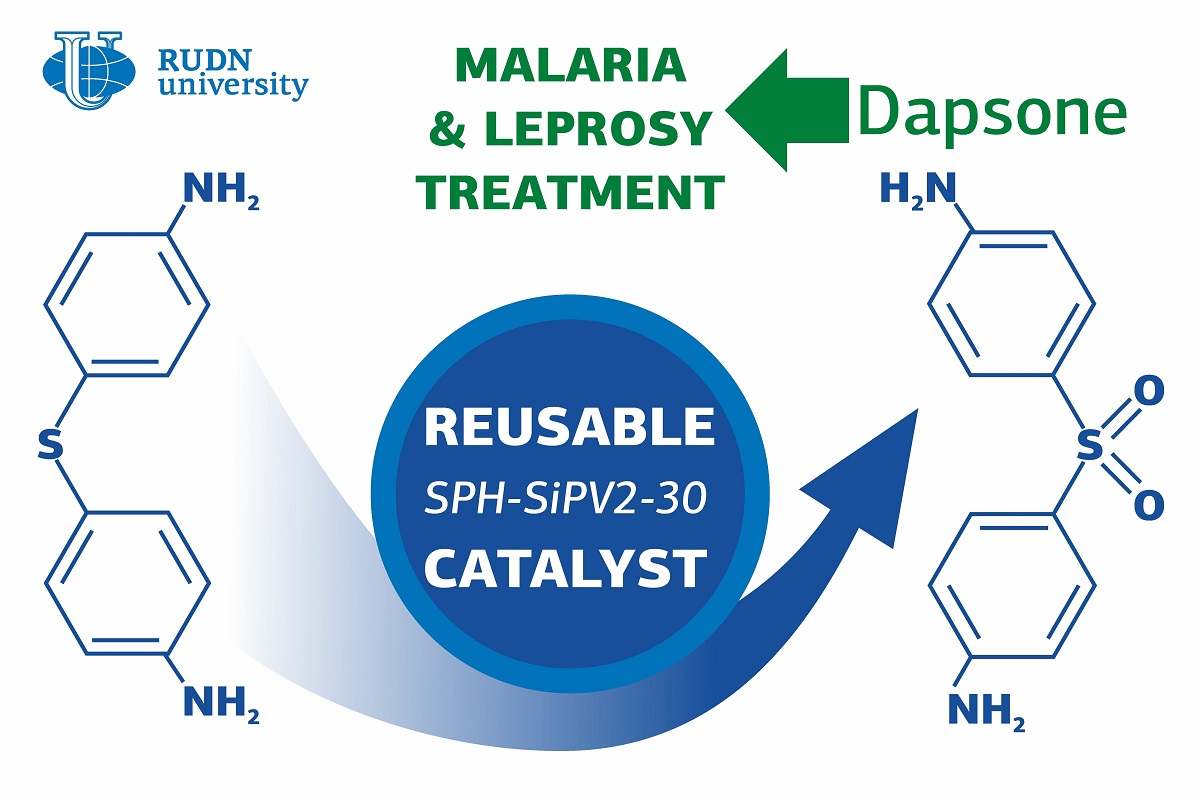

Dapsone or diaminophenyl sulphone consists of two benzene rings with NH2 amino groups. The rings are connected with an oxidized atom of sulfur, or an SO2 group. To obtain dapsone, manufacturers oxidize its precursor in which the bond between the rings is formed by an SH group (sulfur and hydrogen). However, oxidation can also affect sensitive amino groups. Therefore, they have to be protected before the reaction starts—for example, by attaching special protective groups to them. The researcher from RUDN University developed a catalyst that provides for the oxidation of SH groups in the precursor with simple hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide is considered the most environmentally friendly oxidizing agent because its only by-product is water. The reaction of oxidation takes place at room temperature, has only one stage, and requires no protection of amino groups.

“None of the earlier dapsone synthesis reactions can be called completely environmentally friendly as they happen in rigid conditions and have several stages: adding protective groups, synthesis, and their removal. This complexity increases the chances of by-products that should be removed from the reaction,” said Raphael Luke, Ph.D., the head of the Molecular Design and Synthesis of Innovative Compounds for Medicine Science Center at RUDN University.

His team developed a wolfram-based catalyst from polyoxometalates by replacing certain wolfram atoms with vanadium. This increased the acidic properties of the catalyst and sped up the reaction, allowing it to take place even at low temperatures. To prevent the catalyst from being washed off from the reaction, the chemists encased the new compound in a porous material—a hydrogel made of propanoic acid and acrylamide. Thanks to it, the catalyst can be re-used at least three times without losing its efficiency. The team also identified the most optimal synthesis conditions and reagent concentration and managed to reach 100% oxidation of the dapsone precursor at 25℃ in only nine hours.

The results of the work were published in the Microporous and Mesoporous Materials journal.

Products derived from microalgae represent a cutting-edge development in the field of bioeconomy. The potential of this biological resource was discussed at the international research seminar “Foundations for a Green Sustainable Energy”, part of the BRICS Network University’s thematic group on “Energy”. The event was organized by the Institute of Ecology at RUDN University.

Ambassadors of Russian education and science met at a conference in RUDN University to discuss how they can increase the visibility of Russian universities and research organizations in the world, and attract more international students in Russia.

The international scientific seminar hosted by RUDN Institute of Ecology “Experience of participation in student organizations as a way to form career skills” united scholarship recipients of the International Student Mobility Awards 2024 and Open Doors, along with members of the scientific student society “GreenLab” and the professional student association “Kostyor (Bonfire)” shared their projects focused on environmental protection.